Eileen Southern (1920-2002)

Eileen Southern is—and should be—recognized for her many “firsts.” The first Black scholar to earn a PhD in musicology in the United States. Founder of the first long-running academic journal dedicated to Black music. The first Black woman tenured in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. The first Black scholar to publish in the flagship musicology journal in the United States, The Journal of the American Musicological Society.

Accomplishments do not reveal the whole person, of course. Even these accolades cannot convey the depths of Southern’s hard work and sacrifice, her detail-oriented, even exacting, approach to scholarship. Nor do they quite convey her deep love of music and Black culture. Her penchant for tuna sandwiches with onion and her high, clear voice. Her appreciation for the individuals she saw as having paved the way for her to become a “first.”

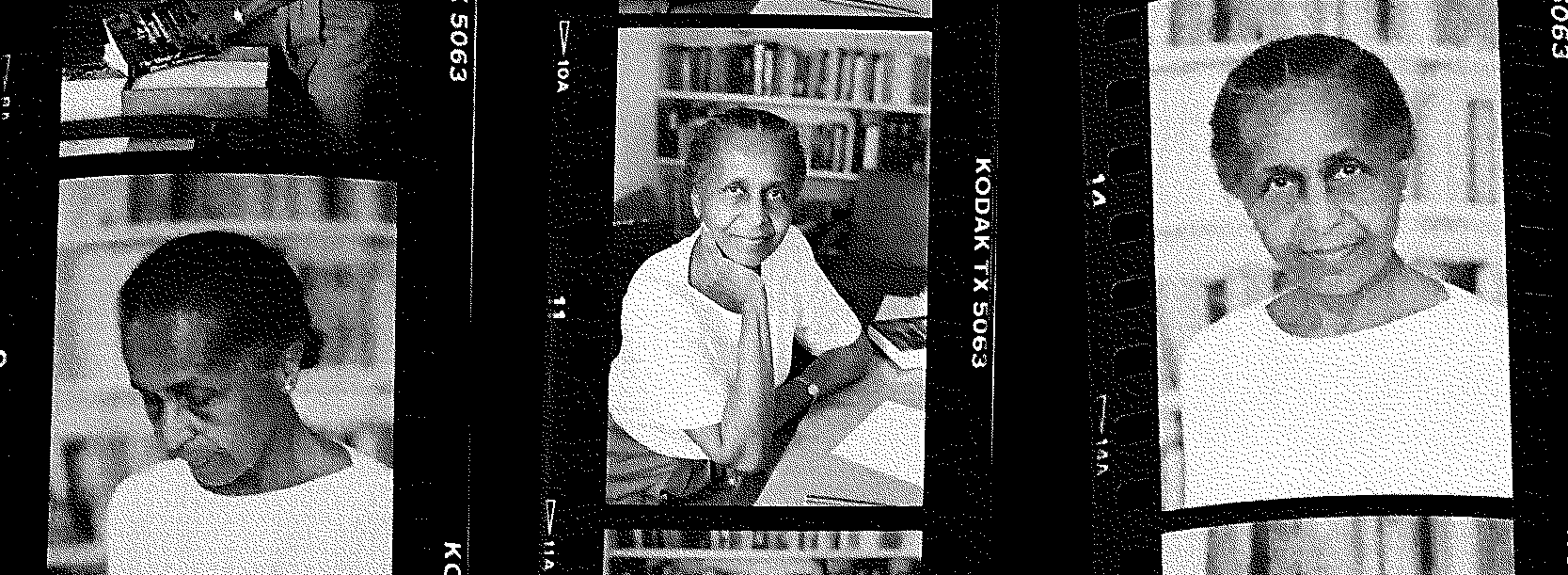

In 1981, the thirteen tenured women in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, all “firsts” in their own ways, participated in an oral history project led by former Harvard/Radcliffe administrator Judith Walzer.2 Here we draw from this interview to outline the life of Eileen Southern—musicologist, mother, pianist, publisher, student, scholar, traveler, trailblazer, wife, writer—built largely on her own words.

-

Southern's interview took place over four sessions in Cambridge, New York, and Philadelphia.↩

“My parents had such a tremendous love of music from the beginning.”

Eileen Stanza Jackson was born on February 19, 1920 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the eldest of three sisters. Her parents, Walter Wade Jackson and Lilla Gibson Jackson, separated when Eileen was about eight years old. Walter was a chemist with a degree from Brown University who taught at Black institutions in the South for several years while his daughters were young. Because of systemic racism, no teaching jobs were available to him in the North. Eileen later pointed to her father as an influential figure in her life who encouraged education and travel as well as working hard and striving for excellence. After separating from his wife, Walter worked as a railway waiter on routes across the upper Midwest and Pacific Northwest while his daughters lived in rooming houses in Minneapolis and Sioux Falls, South Dakota. When Eileen was about eleven, she and her sisters (Elizabeth and Stella) went to live with their mother in Chicago, where they stayed for the rest of their school years.

Five years earlier, or thereabouts, Eileen’s parents had purchased a baby grand piano, which was a major luxury for a family she described as “very poor.” Her mother was a pianist, her father a violinist, and both sang in church choirs. Eileen soon began to study piano and gave her first public concert around age eight. She later recalled a mix of music at home growing up: opera arias, Black folksong, the music of J. S. Bach. “I never got this feeling that this is classical music and this is not classical,” she later recalled. “We just loved music, and I was much older when I learned that people look down on some kinds of music.” She retained this equitable outlook on music for the rest of her life.

Eileen participated in a number of activities while growing up, including the Girl Scouts and Sunday school at her church, but music remained her central focus. Each day began with piano practice from six to seven a.m. and ended with evening practice. In South Dakota as a pre-teen, she served as pianist for a traveling gospel quartet. It was also in Sioux Falls that she remembered a visit by Louis Armstrong, who was there to give a concert around 1930. “Although he was pretty famous then, blacks still couldn’t stay in the hotel, so when musicians came to town to play for white affairs, they usually stayed in this rooming house where we were living.”

After moving to Chicago, Eileen taught piano lessons to younger children at the Abraham Lincoln Center Settlement on the south side of the city (where she took lessons herself) and accompanied a local church choir on Thursdays and Sundays. Eileen described herself as “the class pianist” when she attended Wendell Phillips High School (which served junior and senior high students) through ninth grade. Wendell Phillips was the first Black high school in Chicago and its many well-known graduates included jazz pianist and singer Nat “King” Cole, who was one of Eileen’s classmates. At Lindblom High School, where Eileen attended tenth through twelfth grades, she played piano for gym classes and ballet classes. For her graduation, she played a piano solo during the ceremony: “never in the history of the school had a black child appeared on graduation [day] in any form whatsoever,” and her participation likely caused controversy, she recalled. She estimated she was one of three Black students in a graduating class of six hundred.

At age sixteen, Eileen began to study at the University of Chicago, where she went on to earn two humanities degrees (BA 1940, MA 1941). “I don’t know how I got there,” she mused, “but [I] felt very good about it, since . . . my father had gone there in summer sessions, 20 years or 15 years earlier.” She also studied at the Chicago Musical College (CMC) during this time—her mother encouraged her to leave the University of Chicago and focus solely on piano—but she refused to continue as a full time student at CMC after experiencing “racism . . . so thick you could cut it with a knife.” Eileen did win a Chicago Musical College competition which allowed her to play a concerto movement at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall, “which is like Carnegie Hall in New York.”

“Do you know we still didn't learn everything there was to know about that opera?”

During her Master’s degree coursework, Eileen took a class focused on German composer Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde with Siegmund Levarie, an Austrian Jew who fled the Nazi regime in the 1930s. She was amazed that students could study a single musical work for an entire semester and barely make a dent in all there was to know about it. Her thirst for knowledge and endless curiosity continued throughout her professional career.

Racism shaped Eileen’s career, but did not define it. She spent her first years of postsecondary teaching at historically Black institutions across the southern United States, as opportunities for Black instructors at colleges in the North were extremely rare. Her first such position was at Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College in Prairie View, Texas, about 50 miles northwest of Houston. There she met Lincoln University (Missouri) graduate and business administrator Joseph Southern. The two married in 1942. Over the next decade, the couple moved between Black institutions in the South, with Eileen Jackson Southern teaching at the Second Ward School (a Black public high school in Charlotte, North Carolina), Southern University (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), Alcorn A. & M. College (Lorman, Mississippi), and Claflin University (Orangeburg, South Carolina). She gained valuable teaching experience along the way. As Angela Proctor, archivist of Southern University, shared with our project team:

Southern University, in the majority of cases, provided persons with their first teaching experiences. Persons such as Southern and others primarily received their start at institutions such as Southern University. Institutions like Southern University allowed them to soar and explore and gain the expertise that afforded them the opportunities to continue their studies at much larger and well-known institutions. They leave behind extraordinary legacies for students in the future. This is what Eileen Southern and others did for Southern University.

Southern quickly began to experience the realities of living while Black in the South during the Jim Crow era. She described a move from Mississippi to South Carolina as “just horrible”: staying on college campuses because hotels were not an option, dining in segregated railroad stations because there was nowhere else to eat, not being able to use restrooms at gas stations. “We had a couple of narrow escapes” with whites seeking to enforce the color line, she remembered. When teaching at Southern University, Southern’s attendance at concerts and cultural events in nearby New Orleans was severely limited due to systemic racism and segregation. She turned to books on music, but soon realized she could not comprehend all of the material. “One book that impressed me particularly was a book that was published entitled Music in the Middle Ages [1940] by Gustave Reese . . . I read the book, and I couldn’t quite understand what was going on.” Curious instead of discouraged, Southern began to investigate PhD programs in music so she could learn the skills necessary to understand Reese’s text.

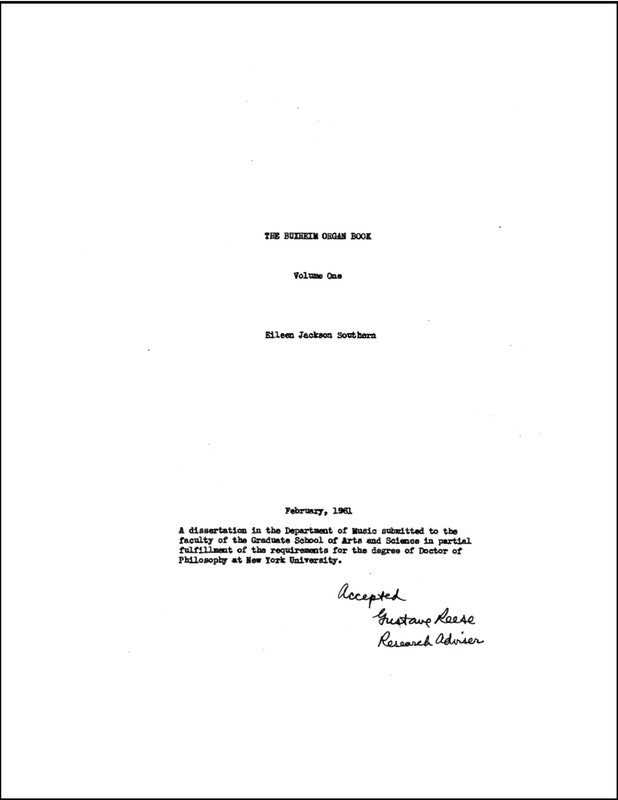

“To make a long story short, I finally got this PhD”

Southern traveled north in the summer of 1951 to visit Harvard University, where she hoped to enroll in the PhD program in music. That program was brand new at the time, graduating its first PhD in 1956. Southern recounted in her 1981 interview that she received “an encouraging letter” in response to her application, and she was led to believe there would be an in-person meeting at Radcliffe College (“at that time you [i.e. women] could only go to Radcliffe”). Upon arrival, however, she recalled being told that a Black woman had already been accepted into a doctoral program for the upcoming year. “Apparently they had decided that one [Black] person was the limit,” Southern recalled. Southern believed that she confronted a quota system, even as such exclusionary practices were not explicit enough to reveal why a rejection had occurred. “I don't know why they didn't write me to keep me from making that long trip there,” she mused. A record of this visit has not yet been located in the archives of Radcliffe College.

Remarkably, Southern next traveled not home, but onward to New York City, where she walked in “off the street” and was accepted in the musicology program at New York University, studying with Gustave Reese, “the star of the department” and author of the book that had so entranced her. The field of musicology was then still relatively new in the United States yet had advanced significantly since her Master’s degree a decade earlier. She found her studies to be challenging, but she loved the work. One course met at the New York Public Library and students had access to the stacks. “It was just heaven being able to go and pick up a book, not waiting for an aide or someone,” she recalled. Southern’s decision to begin a doctoral degree program offered a fresh start in more than one way: documents at the Southern University Archives reveal that a fire had destroyed the Southerns’ on-campus apartment in 1951 and an appeal went out to the entire faculty for contributions to help them recover.3

To fund her degree, Southern worked first at the YMCA on 135th St. in Harlem and then as a music teacher at Stitt Junior High School in Washington Heights and Rockaway Beach Junior High School in Queens. Southern was also raising two children, April (born 1946) and Edward (born 1952). She did not tell anyone at NYU she was married with a family, for fear they would think she was not serious about her studies. She took April to one of her final editing sessions with Reese before submitting her dissertation: “What a shock. All this time he had thought I was single, and here I was bringing this teenage daughter, and I've been married all the time. That was very, very funny.”

-

©The Eileen Jackson Southern Papers, The Archives, Manuscripts, and Rare Books Department, John B. Cade Library, Southern University, and A&M College, Baton Rouge, LA 70813.↩

Though Reese was very thorough in reading Southern’s work, his pace was slow: so slow that Southern seriously considered transferring to the music education program. The doorman at Reese’s building also assumed Southern was a maid and ordered her to use the service entrance on multiple occasions, one of the frequent race-based indignities Southern faced. Eventually, Southern completed her requirements and received her PhD in February 1961.

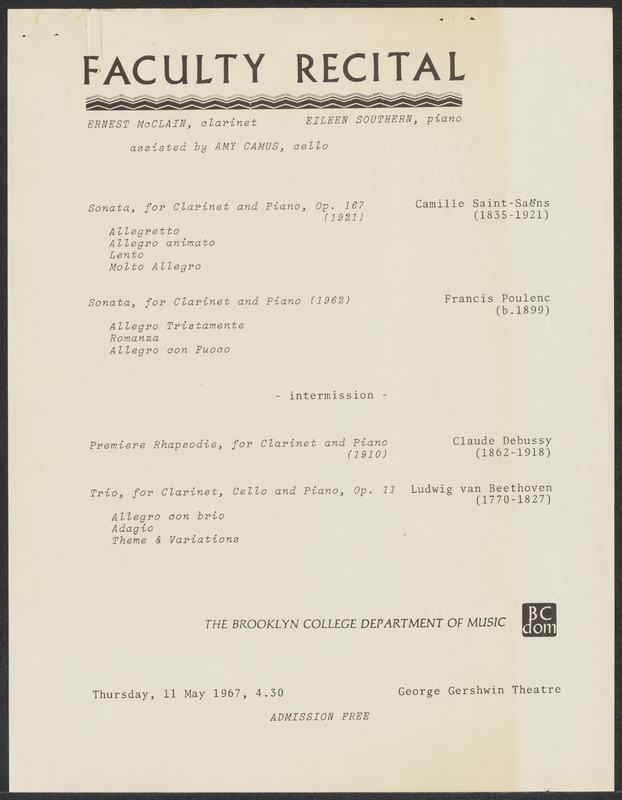

“I also was encouraged enough to build up my repertory to present a recital.”

Both her mother and high school piano teacher hoped Southern would become a professional pianist, but the long hours of practice did not interest her. She knew that such a career was possible, however: “I thought at one time I could become a concert pianist because there had been several black concert pianists who had made reputations,” she remembered, and her performance at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall signaled major accomplishment and professional potential. While teaching in Texas she toured Black colleges and universities as part of a violin-piano duo and as an accompanist for choral groups. Southern later participated in the National Associated Concert Bureau Auditions, and as the state winner from South Carolina (where she was teaching at Claflin University), she performed at Carnegie Hall on January 17, 1948. Though she turned to musicology, Southern continued to devote herself to piano performance and competition well into the 1950s, even while teaching full-time, raising two children, and starting a PhD program.

Southern did not simply continue to perform, but she persisted in studying piano, always seeking to learn and improve. In New York City she studied with concert pianist Ray Lev (1912–1968), who helped her with technique and expression in particular. Lev was a Russian Jew who immigrated with her family to the U.S. in the 1910s. “She was so interested in my talent,” Southern recalled, “so she gave me free lessons.” At a soiree hosted by Lev in the 1950s, Southern met bass baritone Paul Robeson, the only other Black guest in attendance: “I was so thrilled to meet this man and to find that he was so warm and outgoing and concerned about someone of his own color,” she said.

Studying with Lev also gave Southern the courage to participate in a Harlem YMCA recital on New Year’s Day, 1955. “The New Year's Day concerts were very, very popular, very well known and kind of a prestige thing,” she explained. “And I practiced enough. I recall practicing eight hours a day during that holiday season [in order] to be able to present a concert on January 1.” Her efforts paid off, with a rave review in the New York Amsterdam News (January 15, 1955), marveling at how she “held the audience spellbound.”

Southern counted this as her last major recital. “I knew there was no way possible for me to practice the amount of time it takes to do concert work and to do the work that is involved in working for the PhD,” she recalled. Southern continued to give occasional performances, however, such as this 1967 Brooklyn College recital, and she frequently demonstrated at the piano during the musicology courses she taught.

“When I got to Harvard I had been teaching about 30 years.”

Southern joined the full-time faculty of Brooklyn College (City University of New York) in the fall of 1960. She continued to teach there for several years before joining the faculty at York College (also in the City University of New York) in 1969. She began teaching one course per term at Harvard in the 1974-75 academic year and joined the tenured full-time faculty of Harvard in January 1976 as the second chair of the Afro-American Studies department as well as a professor of music. Joseph Southern could not leave his job in New York, and Southern explained in 1981 that “since no efforts were made to help him find a job, he never really thought about moving.” Thus, she commuted for ten years, living near the Harvard Business School during the week, flying to New York on Thursday evening or Friday morning, and driving back on Saturdays. Explaining the arrangement in The Harvard Crimson, the student newspaper, a reporter wrote in 1986 that the Southerns “have shared the five-hour drive every weekend and talked on the phone each night since 1976.”4

Southern was matter-of-fact about her experience at Harvard in her 1981 interview. “I do think that Harvard is very racist,” she told Walzer. “But when I'm saying that, I'm not saying it's different from any other place. What I'm saying is you don't expect it.” Not all racism was overt, she observed (“some of the professors are so much involved in their work that they don’t have time for actively being racist”). But she experienced bias on both macro and micro levels, from a lack of institutional support for the few Black faculty and graduate students to feeling snubbed at parties and receptions. Conflict in the Afro-American Studies department, which predated Southern’s appointment and continued during her time as chair, also made her tenure at Harvard difficult.

-

Meilin Kwan-gett, “The Underside of Academic Opportunity: The Story of Harvard’s Only Tenured Black Woman” The Harvard Crimson (May 2, 1986).↩

There were many parts of her Harvard experience that Southern loved, though. She enjoyed working with students, whom she noted were often surprised that a Black woman was just as knowledgeable as the usual Harvard professor who sported “thick-soled shoes” and “gray hair.” Southern found the Shop Club, a group for faculty to meet and discuss their research in a semi-formal setting, to be “warm and outgoing and accepting.” She described herself as too shy to present a paper of her own, but loved learning about the research of her colleagues from across the university. When NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins received an honorary degree in 1978, Southern enjoyed serving as his faculty escort at commencement. And the funding and opportunities available to Harvard professors were world-class. “Those people in inter-library loan are just marvelous,” she told Walzer. She often worked in the library until it closed at 10:00 p.m.:

I must say the marvelous thing about Harvard is that it encourages you to do research because there's so much going on and everybody's doing something so you want to be a part of it, and the second thing is the time. I had always taught 12 hours a week and to suddenly get into a situation where you have time to do research and the library . . . I spend . . . I must say I must be spending at least 15-20 hours a week in the library. It's just fantastic.

“We lived for the summer when we could travel.”

Southern and her family took a trip in the summer of 1961 to celebrate the completion of her doctorate, and she continued to travel widely (while being mindful of her budget) for the rest of her life. There were road trips across the US and Canada where the family “did a lot of camping because we could pay one dollar a night or two.” In 1963 Southern went to Europe for the first time with her daughter, April, and another relative. Despite being a scholar of European music (which for predominantly white and male musicologists often yielded research trips abroad), Southern recalled that she had “never even thought about going to Europe because I thought Europe was for rich people.” Armed with the guidebook Europe on $5 a Day, the trio crossed the continent. “It was just such a thrill,” Southern recalled. “We learned so much.”

The next summer, Southern returned to Europe with her husband, Joseph. “From that time on, we became a travelling family,” she explained. There were trips to Haiti, to Japan, to Zimbabwe, and to Switzerland. Southern participated in international academic conferences and also traveled extensively to give lectures across the US following the publication of The Music of Black Americans. She credited travel with helping her to grow as a person and change her perspective. “I think Americans tend to be a little provincial,” she told Walzer. “We think we're the only people, and you don't realize all the other kinds of people who have exciting lives out there.”

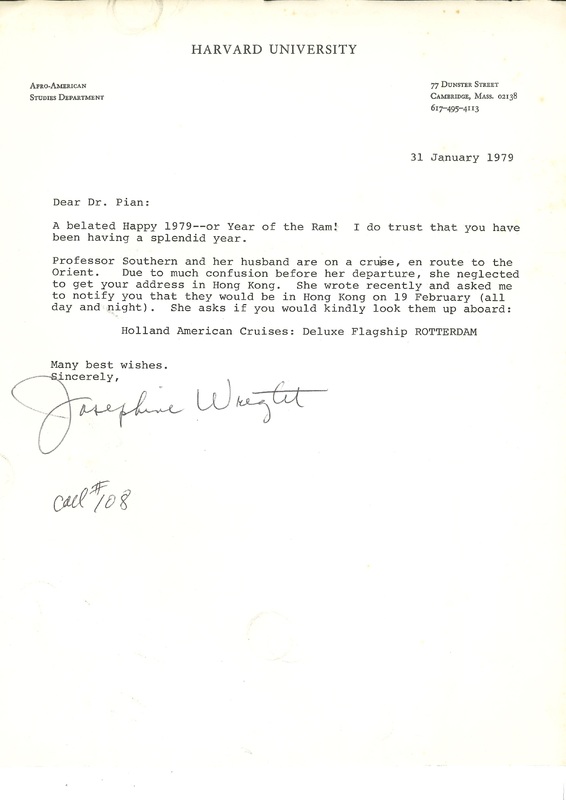

On one of their international cruises, Southern and her husband met up with Rulan Chao Pian (1922-2013), a fellow professor in Harvard’s Department of Music. Pian, who like Southern held a joint appointment (hers in East Asian Languages), shared an office with Southern in the music building. “I think the Music Department is one of the friendliest departments toward women professors and minority professors,” Pian told The Crimson for a May 2, 1986 article. “We have three women. There is no other department like it.” The third was Luise Vosgerchian (1922-2007), the daughter of Armenian immigrants who taught piano and musicianship.

“‘If you make a better mousetrap the world will make a beaten path to your doorway.’”

Throughout her life, Southern drew strength from “folk sayings” such as this one, passed down from her father. “[They] enabled me to feel, ‘well, if I am as good as I possibly can [be], perhaps racism will take second place.’ You know, if I have something to offer that people are really interested in.” At Harvard, she could look to history on days when she needed inspiration. “When from time to time I became too depressed with having to cope with Harvard, I would turn to my role model, W.E.B. Du Bois, and reread his account of his days at Harvard,” Southern wrote in her contribution to the 1993 book Blacks at Harvard. “Like him, I went to Harvard because it was a great opportunity for me as a black female scholar, and I accepted the reality of racial and sex discrimination.”

Southern also drew strength from a host of individuals hailing from many corners of her life: University of Chicago librarian Scott Goldthwaite (“he just encouraged me in every single way”), who crossed racial lines to attend one of Southern’s concerts; the president of Prairie View, W. R. Banks (“I had never seen a black president of a college before”), who offered Southern her first job; Catharine Brooks, one of the first women with a musicology degree in the US (“they weren’t ready for her”), whom Southern met at NYU; Harvard musicologist Elliot Forbes (“the kind of person that would say, ‘Let’s have lunch’”), who was a generous colleague; administrator Phyllis Keller (“she helped keep me sane”), one of Southern’s allies at Harvard. And most of all, her husband, Joseph (“he was so supportive”), who ran the business side of their journal, shared childcare and housekeeping duties in an era when this was unusual, and made breakfast every morning for the entirety of their marriage.

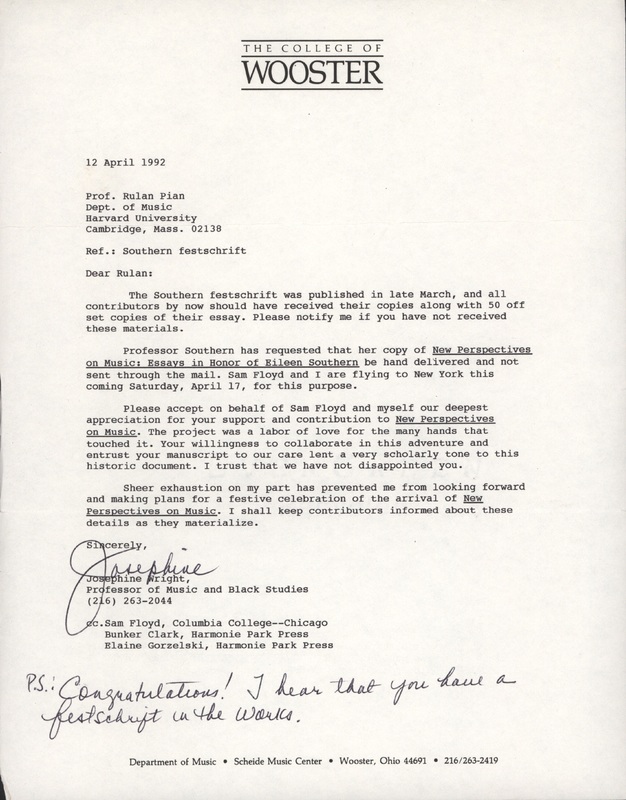

Colleagues, friends, and former students who looked to Southern for support in their own careers collaborated on New Perspectives on Music: Essays in Honor of EIleen Southern, published in 1992. This volume was a Festschrift, part of an academic tradition in which a collection of essays is issued to celebrate a senior scholar close to or after retirement (Southern had retired in 1986). Almost two dozen academics contributed research on topics dear to Southern: Renaissance music, African American music and U.S. traditions of all sorts, folk music, and women in music.

Josephine Wright, Southern’s protégé at Harvard, co-edited the volume with Samuel A. Floyd Jr., director of the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago. In this letter, Wright sends an update about the book to contributor Rulan Pian. (In an interview with the ESI team, Wright explained that she and Floyd approached Harvard’s administration to provide a subvention for publishing the book, asking for support that is traditional for tributes of this sort, and they were turned down. The book ended up being published by Harmonie Park Press in Michigan, through its editor J. Bunker Clark.)

Floyd’s introduction to the book, “Eileen Jackson Southern: A Quiet Revolutionary,” outlines Southern’s career and details what Floyd calls her greatest accomplishments, including the first edition of The Music of Black Americans, “a watershed event” and “the first real musicological study of black music.” He called attention to the radical nature of such a large-scale work on a long-neglected topic of study. It is important not to conflate Floyd’s designation “quiet” with timidity; while Southern described herself as “shy,” she was nevertheless a confident scholar and teacher.

Southern admitted to feeling bitter about some of her experiences at Harvard, but she continued to follow her research interests, delving deeper into the history of Black music in the United States. "I have learned at Harvard not to pay attention to what others might say. You cannot really afford to listen to how others might criticize you, or [how] they might feel your work is unimportant," she told a Crimson reporter in a 1986 interview. Her only regret was that she arrived at Harvard so late in her career. “If I could stay another 10 years, I think I could be responsible for some change,” she said.

Southern may not have changed Harvard as she had hoped: there is much work yet to be done to make this and other institutions more open, just, and equitable.5 Yet when she died in Port Charlotte, Florida in 2002, Southern left behind the legacy of a scholarly field transformed.

-

Leah J. Teichholtz and Andy Z. Wang, “‘Disrespected, Devalued, or Dismissed’: University Affiliates Assess Harvard’s Commitment to Black Scholars.” The Harvard Crimson (May 27, 2021).↩