Eileen Southern in the Classroom

Southern began her teaching career as a teenager, when she gave younger children piano lessons at the Abraham Lincoln Center Settlement in Chicago. She received twenty-five cents per lesson and taught both after school and all day on Saturdays, the latter without a lunch break because, as she recalled, “you had to make as many quarters as you possibly could.” Her own teacher at the settlement, Meda Zarbell Steele (1878-1956), had arranged for Southern and her younger sister to teach other students; Steele, the daughter of Norwegian and German immigrants, recognized Southern’s talent and gave her free lessons, later paying half of Southern’s tuition at the University of Chicago for the first two years of her degree program. Southern paid her own way for the final two years of her BA in the humanities, while teaching at the Settlement “every single minute of the day” to make ends meet. In December 1941, having completed an MA at the University of Chicago a few months previously, Southern accepted an invitation to teach at Prairie View A&M, a historically Black university located 50 miles northwest of Houston.

Southern spent the rest of the 1940s teaching at a series of historically Black institutions across the South, moving every few years with her husband, Joseph. “It was not possible for a black scholar to teach in northern institutions” at the time, as she later recounted in an interview for the Radcliffe Quarterly.”1 At Prairie View, Southern mainly taught piano and continued to concertize, touring HBCUs as part of a violin-piano duo and accompanying singing groups to raise money for the university. She then spent a brief period teaching at Second Ward High School, the first Black high school in Charlotte, North Carolina. Next she moved to Baton Rouge to teach piano, music theory, and music history at Southern University. “This is the first time I really went into the thing I was to become so interested in—music appreciation and music history classes,” she later recalled.

Moving again—this time to Alcorn State College in Mississippi—Southern was frustrated by racialized expectations for the music program: “I’m only supposed to sing spirituals and Negro folk songs. Never sing any other kind of music because whites don’t like you to do that; they only want you to sing spirituals.” Southern stayed in Mississippi for a year, then relocated to Claflin University in Orangeburg, South Carolina. There, she designed and implemented the curriculum for the new music major. She returned to Southern University for a few more years, and during this time, she began to think about heading North, both so her daughter, April, would not be raised in the South (“the racism there was just flooring me”) and because she wanted to continue studying music history. Southern University did not subscribe to musicology journals, and Southern worried that she was falling behind in the field she loved.

-

Sara Taber and Jessica Ancker. “Women Professors at Harvard: ‘The Most Doggedly Persistent.’” Radcliffe Quarterly 72, no. 3 (September 1986): 10-13. ↩

New York City

Southern next enrolled in the PhD program in musicology at New York University in January 1952, intending to study European Renaissance music with scholar Gustave Reese. Southern looked to teaching as a way to fund her graduate work: she recalled not knowing about the assistantships that often funded graduate students. It took her two years to qualify as a teacher with the New York City Public School system, which she did in time for the 1954 academic year. Only later did she realize she could have worked as a substitute teacher as soon as she settled in the city.

In 1954, Southern began teaching eighth grade full-time at Stitt Junior High School on West 164th St. in Washington Heights. At the same time, she was enrolled in classes to complete her PhD requirements and the arrangement was taxing. “You can imagine what condition I was in after wrestling with eighth graders all day long and then to try to listen to [Gustave Reese] talk about Dufay and Josquin and everything,” she recalled. At the time, the NYC public schools often combined two music classes, which meant that two teachers were in charge of, in Southern’s words, “75 or 80 wiggling, squirming adolescents who were not very much interested in what you were trying to do.” To settle the students down, Southern had them copy song lyrics from the chalkboard at the beginning of class. Compounding her challenges, the few textbooks available at Stitt Junior High were 20 to 30 years old. After a few years, Southern was able to lead a student choral group, which staged operettas in the school auditorium. Her final two years of public school teaching were at Junior High School 180 in Rockaway Beach, Queens, closer to her home in St. Albans and to the school where her husband taught. JHS 180 was a new school and as a result Southern taught music without pianos for her first year. The student population was largely white, mostly made up of middle-class Jewish students. The change from her school in northern Manhattan was striking: she noticed how “the children were encouraged to express themselves and to talk” whereas “at the black school the children were forced to be quiet.”

In both schools, Southern tried to introduce music theory where she could, and she also taught English “to stay in touch with the written word.” Southern’s fellow teachers in the public schools, who were majority white, “didn’t expose the children to any classical music whatsoever,” which Southern sought to rectify. She taught students at both schools “Where E’er You Walk” from Handel’s Semele, folk songs, and the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” “The white children loved it like the black children . . . I didn’t make a big fuss. I wouldn’t say this is a song by a black composer,” she explained. “I would just teach them the song, and if they never realized he was black I didn’t care, but I just wanted them to be exposed to different kinds of music and not only Broadway junk.”

One of Southern’s professors at the University of Chicago, Siegmund Levarie (1914-2010), had since become chair of the music department at Brooklyn College, and he invited her to lecture for the 1958-59 school year. Thus, while continuing to teach junior high school full time, Southern also taught a music education course there, as “none of their music teachers had ever taught in public schools.” She was then ABD (all-but-dissertation in a PhD program), and she joined the faculty as a full-time lecturer in 1960, at first teaching music education courses. “I figured you know, you have to crawl before you can walk, and I thought if I just could stick in there, I would eventually get to teach in the field of my interest,” she said. Southern completed her PhD in 1961, and she became an assistant professor in January 1964. Eventually, she was asked to serve as deputy chair of the graduate program, at the same time as did not feel she was advancing as quickly as she should have been, despite her qualifications. “People were coming to the department who did not have PhDs, who had not published, and they were getting promotions and I was being passed over,” she recalled.

Her experiences with some colleagues at Brooklyn College left Southern feeling “unwanted, and worse, unneeded,” as she reported in a letter to Levarie in May 1967. The circumstances of this complaint are unclear—as are the names of the faculty involved—but it documents how at a certain point Southern decided to withdraw rather than face constant micro- and macro-aggressions. One such instance took place after this letter. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968, students demanded courses on Black culture, and Southern began to develop the department's first course on Black music. She was eventually informed, however, that another member of the faculty would be teaching it. “I asked the chairman about teaching the course, [and] he said, ‘Well, no we don't want you to teach the course because we are afraid you will make it too scholarly and too’—I’ve forgotten the words he used—but he meant that it would be of too-high quality, and we want a very low level course. So they gave it to one of my colleagues to teach, who knew nothing about black music but which is obviously what they wanted.”

In 1969, Southern joined York College, a brand new school that was also in the CUNY system, as an associate professor—a promotion above her previous appointment. Having been unhappy at Brooklyn College, she viewed the opportunity to organize the music program as “heaven . . . such luck” in her words. She sought to differentiate the new program from the other CUNY senior colleges and did so by emphasizing contemporary music and jazz and starting a gospel choir. She grew discouraged, however, as the university was slow to get up and running, to build an arts building and a library. Southern even returned to teaching piano lessons for beginners.

While Southern was teaching at York College, W. W. Norton published the first edition of The Music of Black Americans (1971), and she began to be sought out for advice about Black music, both from her own students and also from students and researchers across the country and around the world. In February 1975, Southern received a letter from Gerard Gonnelly, a student at City College (CUNY) who was studying the African American violinist Clarence Cameron White (1880-1960). Gonnelly told Southern that The Music of Black Americans “was the first source I went to for information on this gentleman” and Southern provided him with several suggestions of where to turn next.

Southern’s sphere of influence with students grew even larger by the mid-1970s, when she began to teach part-time at Harvard. She had met Ewart Guinier, a labor activist and chair of Harvard’s relatively new Afro-American Studies Department, at a meeting of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and Guinier asked her to teach at Harvard as a lecturer. Southern agreed, and beginning in the fall of 1974 she taught “Afro-American Studies 135a. History of Afro-American Music.” Still living in St. Albans, Queens and working full-time at York College, Southern commuted to Cambridge to teach every Monday.

Harvard: Afro-American Studies Department

At Harvard, Southern joined a department that had been established just six years previously. On April 10, 1968, Black students had published an advertisement in Harvard’s student newspaper, The Harvard Crimson, articulating four demands in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination:

1. Establish an endowed chair for a Black Professor

2. Establish courses relevant to Blacks at Harvard

3. Establish more lower level Black Faculty members

4. Admit a number of Black students proportionate to our percentage of the population as a whole

In January 1969, a committee that had been formed to generate a plan for African Studies and Afro-American Studies at Harvard published its findings, known as “the Rosovsky report” and named after its chair, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Henry Rosovsky. It recommended formation of a standing committee to grant undergraduate degrees in Afro-American Studies. Following student protests in April 1969, Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) reversed course and voted to make Afro-American Studies a department, not simply a program with limited institutional heft. The faculty also agreed for students to serve on the department’s executive committee, which among other roles was in charge of appointing faculty. In 1972, that student privilege was revoked.

In the spring term of 1976, Southern joined the Harvard faculty as a full professor, becoming the first African American woman tenured in Harvard’s FAS. At the same time, she was appointed chair of what was then called “Afro-American Studies.” In her role as chair, she stepped into a volatile bureaucratic and political situation that remains difficult to unpack. Here we share Southern’s perspective, continuing to draw on her 1981 interview.

When Southern arrived at Harvard, not only did she stand out as African American, but women were also a marginal presence on campus, with Harvard and Radcliffe only having fused their admissions in 1975. Southern had not sought the role of chair, but instead was asked by Ewart Guinier (the department’s first chair), FAS Dean Henry Rosovsky, and President Derek Bok to do so in anticipation of Guinier’s retirement. “Everybody I knew was insistent,” she later recalled. “They thought it was such a great idea. Nobody thought about the sacrifice I would have to make leaving my home and everything.” Southern felt she was perceived by many students, junior faculty, and staff to be an outsider, even “a ‘creature’ of the administration,” as she recalled. Coming from York College, which was largely white, Southern was not used to Black students’ vocal demands for the new Afro-American Studies Department: “The students wanted to have a meeting with me [when she began as chair] and tell me exactly what they expected from me and what it was I had to do and everything,” she recalled. As the department found its footing, students, faculty, and administrators faced a series of questions about its scope and direction: Should activism and community engagement be a core tenet of the curriculum? How should the study of Afro-American issues relate to that of Africa and the Caribbean diaspora? Should students have a say in running the department? What was the best way to attract and retain tenure-track faculty?

Southern soon felt herself caught between Guiner’s and Rosovsky’s visions for the department; she also felt the institution provided her with limited guidance. “I knew nothing about Harvard tradition. It’s a very unfair situation for a woman, a Black woman to be placed in a leadership role who had never been to Harvard,” she recalled. Indeed, Southern was one of just two women chairing FAS departments at the time, the other being Luise Vosgerchian in the Department of Music. Southern did receive advice from what she later called a “shadow advisory committee,” which helped her with decisions, but that group was not publicly acknowledged in order to minimize confrontations about how the department was being run.

During her three calendar years as chair, Southern brought many changes to the Department of Afro-American Studies. She began a quarterly newsletter, Nimba; implemented general examinations for concentrators (majors); ironed out course requirements; began a lecture series, in her words, “to bring scholars to the campus so that the students would have role models”; and set up a colloquium for junior faculty to present their work to one another. She replaced Guinier’s model of having multiple part-time lecturers with one employing more full-time instructors who “would have some interest in the program . . . and be there for the students to talk to.” Southern detailed many of these developments in a 1976 report which responded to recommendations from a 1972 Third-Year Review Committee (“McCree Report”). She cited a lack of cooperation from other departments in response to her attempts to integrate Afro-American Studies into the FAS community and also noted that there were at the time of her writing fewer tenured faculty instead of more, as the 1972 report had charged.

Southern felt that her time as chair was filled with conflict. Some of the issues, as she perceived them, stemmed from the fact that she followed recommendations in the McCree Report even though some students and junior faculty did not agree. The report suggested the following: “a focus on the social sciences and humanities”; “a greater emphasis on Afro-American rather than African Studies”; a primary focus on academics, not “community activity”; student representation on all committees except those involving faculty appointments; and the appointment of more tenured faculty. Several students voiced their opinions in letters to The Crimson, decrying what they felt to be an unjust sidelining of Africa as well as “the political and socio-economic aspects common to blacks in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas.”1 Others complained that their participation in department governance was not welcomed. “She rules the department autocratically, and does not take kindly to any questioning of her decisions,” concluded one opinion piece by two Black concentrators.”2

Despite Southern’s efforts, a visiting committee tasked with assessing the department at the end of her time as chair recommended the department be abolished. “The only real criticism that they had, which hurt me very much,” she recalled, “was that the department was black. That hurts me tremendously . . . over and over again they talked about the fact that it was a black enclave and they didn't like the idea of its being a black enclave. And I think that's so ridiculous because it's a black studies program, and you would think that the black input would be what it was.” President Bok and Dean Rosovsky were determined to keep the department going, Southern recalled, “but in the meantime, I was completely exhausted. Emotionally, physically, everything. And I had completed three years, which was the understanding—that I would have a three year appointment as a Chairman. So, I went to Henry [Rosovsky] and I told him, and he knew that it had been a very trying three years because I shared all my problems with him which was what you were supposed to do. He was very sympathetic. He said, ‘Ok. You can have a leave.’ So, I took a leave, January to June, 1979.”

In Southern’s absence, which coincided with the ten-year anniversary of the on-campus student protests that had taken place in 1969, many of the junior faculty in Afro-American Studies held meetings and demonstrations, and in Southern’s words “tried to stir up the students.” She recalled: "I think I'm rather militant, and most whites think I'm militant, but blacks-you know, I wasn't out there screaming and yelling, and I've never done that. They really had it in for me. They decided that they were going to get rid of me as the chairman and run the department themselves.” Instead, Rosovsky suggested that the department begin a period of dual leadership, with both a governing committee (chaired by Black law professor C. Clyde Ferguson) and Southern as department chair. Southern disagreed with many aspects of this decision, including having someone from a professional school make decisions about an undergraduate curriculum, and she decided not to accept a reappointment as chair. She instead began to withdraw from the department: “The more I thought about it and the more hostile became my personal environment, the more I decided that it would just be better for me to remain aloof.”

Harvard University Department of Music

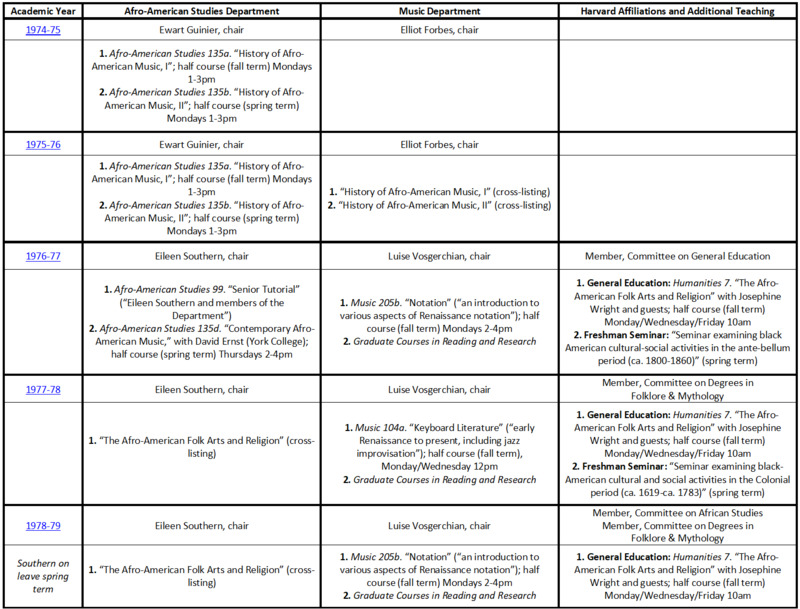

Southern taught a wide range of courses during her time at Harvard: freshman seminars, general education courses and seminars for undergraduates, tutorials, and graduate seminars. While many of these courses were in the Afro-American Studies Department, all were related to music in some way. Within the Department of Music, Southern taught at least one course on European music each academic year.

These tables detail Southern’s teaching at Harvard, with the information drawn from the Courses of Instruction catalogs at the Harvard University Archives.

Southern also served as a member of several dissertation committees in Music (Afro-American Studies did not begin a graduate program until 2000). She had been a committee member for Edward A. Berlin's dissertation on piano ragtime at the City University of New York in 1976,1 but none of the Harvard students wrote about Black music, and she did not appear to serve as primary advisor for any of them:

Thomas Whitney Bridges (historical musicology, 1981), “The Publishing of Arcadelt’s First Book of Madrigals”

Advising committee: John Ward, Lewis Lockwood, Eileen Southern

James M. Meadors Jr. (historical musicology, 1984) “Italian Lute Fantasias and Ricercars Printed in the Second Half of the Sixteenth Century”

Advising committee: David Hughes, Lewis Lockwood, Eileen Southern

Keith Austin Larson (historical musicology, 1986) “The Unaccompanied Madrigal in Naples from 1536 to 1654”

Advising committee: John Ward, Anne Dhu Shapiro, Eileen Southern

Amy Stillman (ethnomusicology, 1991) “Himenetahiti: Ethnoscientific and Ethnohistorical Perspectives on Choral Singing and Protestant Hymnody in the Society Islands, French Polynesia”

Advising committee: Rulan Pian, Eileen Southern, Adrienne Kaeppler

In the fall term of 1981, Southern was asked to teach the first semester of the survey of Western music history for undergraduates, a bread-and-butter course for any music department. She was both frustrated, feeling she had been asked as a last resort because no one else was available, and thrilled to be teaching a foundational course in her discipline, which she had not yet had an opportunity to do at Harvard. “I’m enjoying it tremendously,” she told Judith Walzer. Teaching part of the survey also meant having a larger class enrollment; Southern’s electives generally had few students, which she attributed to racism. “I haven’t had that many white students or that many black students either,” she asserted at the time, “because black students have the same stereotypes. They just don’t believe you could possibly know anything if you’re a black [professor] . . . I think both black and white students need to see blacks in the classroom and teaching in every area. That's why I'm excited about the European music because it's not just enough to teach from the black experience, although that's very important, but you should teach where you're trained.”

With the Department of Music, Southern joined a faculty that was at once unusual for its day, with more tenured women than any other department at Harvard, and typical, with racism and sexism both active issues. Southern told Walzer that she experienced “a few difficulties in regard to acceptance” in Harvard’s Music Department, but that she felt the same way at Brooklyn College. “My life [in Music] has been tolerable. Not always pleasant, but tolerable,” she stated. Of some department members she said: “It's very difficult to put this in words . . . they just don't have anything to say or anything. It's hard to put in words how racism—this is a kind of insidious racism.” At the same time, several faculty members became friends and allies.

One of Southern’s closest colleagues in the music department was John Ward (1917-2011), who, like Southern, was a Renaissance scholar and had studied with Gustave Reese at NYU. At the few Harvard gatherings Southern attended, she and her husband Joseph would form a conversational quartet with Ward and his wife, Ruth. “John Ward . . . has just been marvelous,” she said in 1981. “On every occasion he has treated me as a colleague, and it just means so much to you to have one person that respects you. If he didn’t I’d have no way of knowing.” Southern’s letters to Ward from their retirement suggest not only shared research interests but a warm friendship. In the letter below from May 1992, Southern writes to Ward with evident delight upon receiving a copy of her Festschrift, telling him how his contribution reminded her of a 1979 trip to Japan and resonated with some of her own research on Black musical theater.

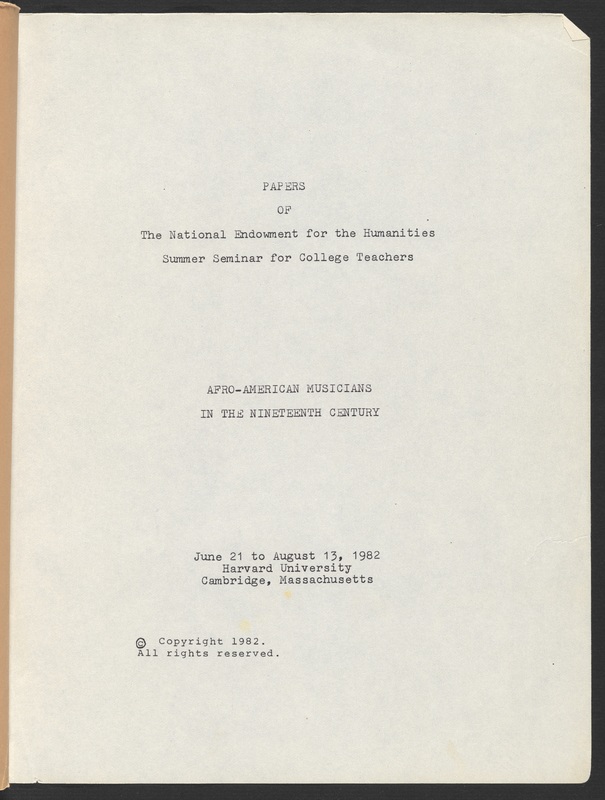

Southern was also involved in teaching projects outside of Harvard’s standard academic year. As one example, she hosted two summer seminars at Harvard for academic professionals, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. One took place in 1982 and the other in 1986. Participants in the initial seminar—three women and eight men—bound their typescript papers into a hefty volume. Their names are: Eleanor Z. Baker, James Roland Braithwaite, Ellistine P. Holly, William J. Jones, Carolyne Lamar Jordan, Justin Kelly, Robert F. Nisbett, Thomas L. Riis, Louis D. Silveri, Paul O. Steg, and Clifford Edward Watkins.

Southern retired from Harvard at the end of the fall term in 1986. Here Christoph Wolff, who was department chair at the time, writes to colleagues as the search for Southern’s replacement began.

Southern continued to contribute to the field even in retirement. For example, she served as a member of a visiting committee to the Williams College music department in 1988, taking part in a routine assessment process.

As the first African American woman tenured in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, as the chair of the relatively new and politically contested Department of Afro-American Studies, as a scholar of Black culture in a Music Department devoted largely to study of the white European canon, as one among 13 tenured women in FAS—as a vanguard figure in multiple dimensions—Eileen Southern had mixed experiences at Harvard, and she was remarkably open in discussing the issues that she faced. In addition to the extended interview with Judith Walzer that is quoted here, she shared her experiences in other venues, including an interview in Radcliffe Quarterly in September 1986, where she recounted that it was “difficult at times” to be a “double minority” on the Harvard faculty—an identity that today is defined as “intersectional.”5 She looked back on her chairship of Afro-American Studies as “my most trying experience.” While she found the students to be “stimulating, challenging, and extremely bright” she also perceived that they regarded male professors more highly. Yet there was hope, as she continued: “students have told me that I am an important role model for them. They say, ‘If she can become a full professor and publish books,’ things they normally associate with men, ‘then I can, too.’ And it seems that I can be a role model for white as well as black women.”

-

Sara Taber and Jessica Ancker. “Women Professors at Harvard: ‘The Most Doggedly Persistent.’” Radcliffe Quarterly 72, no. 3 (September 1986): 10-13.